Wells

This page is an overview of all the wells on Venice. For a typical well, see Well

Wells were the primary drinking sources in Venice between the 11th century and the 19th century. There are more than 5000 cistern wells under the streets of Venice, but their wellheads have almost all been removed or destroyed, leaving only 260 remaining wellheads in Venice. These wells no longer serve any functional purpose but still exist beneath the streets of Venice.

A Venetian Well Structure [1] | |

| Number of Mainland Wells Recorded | |

|---|---|

| Total | 234 |

| Cannaregio | 52 |

| Castello | 58 |

| Santa Croce | 21 |

| San Marco | 48 |

| San Polo | 23 |

| Dorsoduro | 29 |

| Giudecca | 3 |

| Number of Wells on Outer Islands of the lagoon | |

| Total | 26 |

| Burano | 2 |

| Chioggia | 2 |

| Lido | 4 |

| Murano | 6 |

| Pellestrina | 6 |

| Torcello | 6 |

Pre-Cistern Wells

As a collection of islands surrounded by a salt-water lagoon, Venice lacks natural sources of freshwater. As a result, Venice had to find alternative ways to obtain freshwater for the city. Before the introduction of the cistern system of Venice, the citizens of Venice relied on a few different sources of freshwater. They caught rain in basins, ran barges to the mainland to collect water from groundwells, and dug shallow wells in the lido to reach pockets of drinking water. These pockets were the result of rainwater filtering through the fine sands of the Lido beaches. Although these sources brought freshwater, they came with many drawbacks. This system mainly relied on the barges to supply water to the city, which was very expensive in both manpower and resources.

The Cistern System

The oldest known Venetian cistern-wells were constructed in the eleventh century, around 1038 [2] , and were spread out across the Venetian landscape. The construction of the cistern system allowed the people of Venice to gather water without needing the barges to transport it from the mainland [3] . These "wells" were actually cisterns that emulated the natural filtration of the Lido's sand dunes. They collected rainwater through street-level drains, filtered it through layers of sand from the Lido, and held the drinkable water to be collected for later use. This system was implimented slowly throughout Venice for the next two hunder years. Then, in the 13th-15th centuries, the city of Venice built wells in every campo and corte to make clean water as accessible as possible. Once the wells became commonplace, Venice's reliance on the water-carrying barges reduced greatly. The barges were not fully eliminated, however, since they were in charge of filling the wells with water from the mainland when the wells began to run dry.

The water in the public cisterns was free for anyone to use, and proximity to water was a great signifier of power in Venetian society. Wealthy citizens would commission guilds to build private wells to separate themselves from the rest of the population or to display their opulence. There were also many private wellheads located in religious buildings. Priests and other leaders closely and strictly supervised the use of wellheads, allowing limited accessibility to the wells a couple of times per day [4] .

While the cisterns were vital to the survival of Venice, they did not come without their drawbacks. Their construction was very difficult, requiring the use of multiple different trades, and there was a risk of contamination to the well water. In 1575, there was an epidemic that took out nearly a third of Venice's population (Seindal, 2023). Earlier this year, there was an unusually high flood that let saltwater seep into the wells' drains and some wells' lids. The saltwater and freshwater mixed to create “a certain muddy mixture so foul that it caused illness”[5]. Despite efforts to clean out the wells, some of the saltwater remained and mixed with the new freshwater as it came in, drawing out the epidemic. After 15 months of consuming the contaminated water, the sickness worsened. Although the public health officials were fast in their action, the city's doctors ignored the symptoms and neglected poor patients [6]. The neglect allowed this illness to turn into the worst epidemic in Venetian history, killing around a third of the population. This epidemic left Venice with a heavy focus on finding a better water source than the cisterns in order to avoid an incident like this happening again.

This was Venice's system for fresh water supply until 1884, when the Venetian aqueduct was constructed, providing Venice with a more reliable and safer source of drinking water [7].

Function

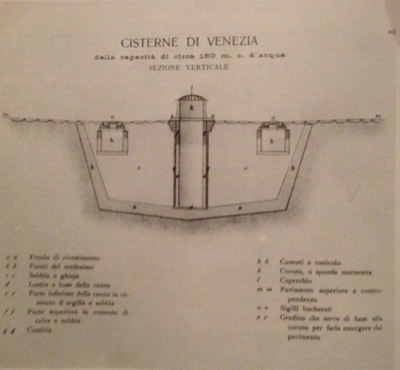

A typical Venetian well has a clay basin that stores rainwater underground and a wellhead to retrieve the water from above ground. Rainwater collects through street-level drains, filters through fine river sand, and then accumulates at the bottom of the basin. The water is filtered again as it travels through the brick lining the well shaft. Then, citizens could retrieve water through the street-level wellhead.

For more information, see well

Map

The location of the wells, along with its wellheads, are designated by red dots on the map.

See Also

Reference

- ↑ "Venice: The Basics". Gambier Keller, 2010

- ↑ Veikou, 2022

- ↑ D. Gentilcore, "The cistern-system of early modern Venice: technology, politics and culture in a hydraulic society", Water History, 13-3 (October 2021): 375-406

- ↑ Venetian Wells, n.d.

- ↑ Raimondo, 1576

- ↑ Benedetti, 1577

- ↑ A city on the water but without fresh water,” n.d.

- ↑ Rizzi, 1981