Wells

This page is an overview of all the wells on Venice. For a typical well, see Well

Wells were the primary drinking sources in Venice between the 11th century and the 19th century. There are more than 5000 cistern wells under the streets of Venice, but their wellheads have almost all been removed or destroyed, leaving only 260 remaining wellheads in Venice. These wells no longer serve any functional purpose but still exist beneath the streets of Venice.

A Venetian Well Structure [1] | |

| Number of Mainland Wells Recorded | |

|---|---|

| Total | 234 |

| Cannaregio | 52 |

| Castello | 58 |

| Santa Croce | 21 |

| San Marco | 48 |

| San Polo | 23 |

| Dorsoduro | 29 |

| Giudecca | 3 |

| Number of Wells on Outer Islands of the lagoon | |

| Total | 26 |

| Burano | 2 |

| Chioggia | 2 |

| Lido | 4 |

| Murano | 6 |

| Pellestrina | 6 |

| Torcello | 6 |

History

As a collection of islands surrounded by a salt-water lagoon, Venice lacks natural sources of freshwater. As a result, Venice had to find alternative ways to obtain freshwater for the city. Before the introduction of the cistern system of Venice, the citizens of Venice relied on a few different sources of freshwater. They caught rain in basins, ran barges to the mainland to collect water from groundwells, and shallow wells dug

barges of water from the mainland to supply the people of the city with water.

The oldest known Venetian wells were constructed in the eleventh century [2] , and were spread out across the Venetian landscape at first. In the 13th-15th centuries, the city of Venice built wells in every campo and corte to make water as accessible as possible.

The water in the public cisterns was free for anyone to use, and proximity to water was a great signifier of power in Venetian society. Wealthy citizens would commission guilds to build private wells to separate themselves from the rest of the population or display their opulence. here were also many private wellheads located in religious buildings. Priests and other leaders closely and strictly supervised the use of wellheads, allowing limited accessibility to the wells a couple of times per day (Venetian Wells, n.d.).

Venetians depended heavily on this system for their fresh water supply until 1884, when a modern water supply system was established [3]

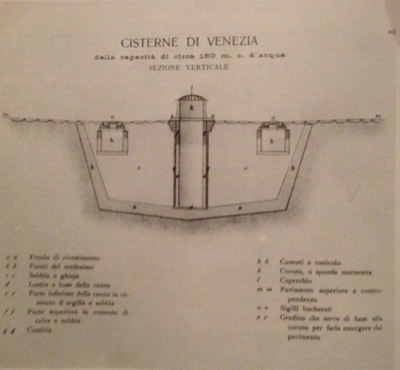

In the 11th century, the construction of the cistern system allowed the people of Venice to gather water without the need for people to deliver water from the mainland to the city [4] . While the government of Venice created enough public wells for the population, wealthy venetians would commission their own private cisterns so that they could separate themselves from the rest of the population. The cistern system works by capturing rainwater through gully grates made from Istrain stone. These grates had holes allowing for water to fall through. The captured water would then collect in underground tanks called galleries made from brick, cassone. A large area about 3-4 meters deep filled with sand, spongia, and lined with impermeable clay would filter the water as it moved to the center of the cistern. In the center of the cistern was a well shaft, canna, made from a semipermeable brick called pazzoli and semipermeable mortar. This is where the water accumulates and people can bring up the water from the wellhead.

Access to a well meant Venetians did not need to pay for barges of water. This, however, did not eliminate the need for the barges as they had the job of topping off the wells when they began to run dry. Well water was also very clean for the time as filtered rainwater is usually safe to drink. The water in the public cisterns was free for anyone to use so it did not cost the population anything to acquire water. Access to water was a great signifier of power in Venetian society. If one were wealthy enough to afford it, one could build their own private well, giving that person complete control over the water from that well, barring certain people from drawing water from the well.

While the cisterns were vital to the survival of Venice, they did not come without their drawbacks. Their construction was very difficult, requiring the use of multiple different trades to complete their construction, meaning the only people capable of building private wells were the wealthy. There are also many private wellheads located in wealthy and religious buildings. Priests and other leaders closely and strictly supervised the use of wellheads; they were the only ones who had keys for these structures and limited accessibility to them a couple of times per day (Venetian Wells, n.d.). Some believe that this system allowed Venice to grow and thrive for many centuries, others believe that this system created social boundaries and that “water followed the spatial divide between rich and poor areas” (Valenti, 2024).

Function

A typical Venetian well has a clay basin that stores rainwater underground and a wellhead to retrieve the water from above ground. Rainwater collects through street-level drains, filters through fine river sand, and then accumulates at the bottom of the basin. The water is filtered again as it travels through the brick lining the well shaft. Then, citizens could retrieve water through the street-level wellhead.

Map

The location of the wells, along with its wellheads, are designated by red dots on the map.