Buildings

Buildings

The built environment of Venice reflects centuries of architectural evolution, adaptation, and shifting patterns of residential and economic activity. This page provides an overview of how Venetian buildings are classified, how they are used today, and what recent analyses reveal about their structure, height, residential capacity, and vacancy. It incorporates extensive measurements, geospatial analysis, and modeling to improve building-scale understanding across the historic center.

Building Types & Classification

Overview of Venetian Classification Systems

Venice classifies its buildings through a structured system that identifies architectural typology, construction period, and predominant functional characteristics. This classification helps describe when, how, and for what purpose each building was constructed, enabling a clearer understanding of the city’s urban fabric and its evolution.

For more details on individual building types, uses, and classification logic, see this page (https://wiki.cityknowledge.org/index.php/Building). This page provides comprehensive descriptions of Venetian building categories, examples of each type, and further technical documentation that complements the classification system summarized here.

Architectural Typology (Tipologia Edilizia)

Architectural typology identifies building form, organization of interior space, and structural hierarchy. Typology categories include long-standing Venetian forms such as monocellular, bicellular, tricellular, polycellular, unitary, modular, and shed structures.

These typologies were essential to our models because different types exhibit distinct relationships among measured height, floor height, and the expected number of floors.

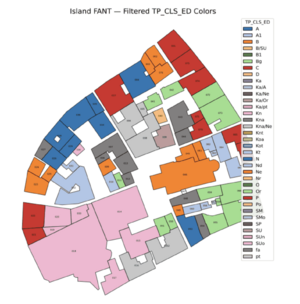

This map illustrates a block of buildings on the island of FANT, with each building footprint color-coded by its architectural type. The different colors represent variations in construction period, structural form, and intended use, allowing for easy visual comparison of how architectural types are distributed within a single urban block.

Building Use Analysis and Spatial Visualization

Understanding how Venice’s buildings are used—residential, tourist-oriented, mixed-use, or vacant—is essential for analyzing depopulation, housing availability, and long-term urban sustainability. Our analysis combines architectural classifications, building-level fieldwork, and ArcGIS-based spatial modeling to create the first citywide, building-specific visualization of residential, non-residential, and vacant space across Venice. This unified dataset and accompanying maps form the basis for a continuous monitoring system for urban change in the historic city center.

Estimating Residential Units and Building Use

Residential unit estimates were derived using a unit & residential estimation model that merges:

Water meter data (number of units per meter, tariff type, and consumption)

Livable volume estimates (footprint × estimated residential floors)

Census-unit totals (to ensure tract-level consistency)

Observed proxies: doorbells, shutter status, ground-floor use

Water data also allowed us to distinguish between:

Primary residences (residential tariff, active usage)

Secondary residences / STRs (higher tariff, intermittent usage)

Vacant units (≤0.5 m³ annual consumption, validated through shutter data)

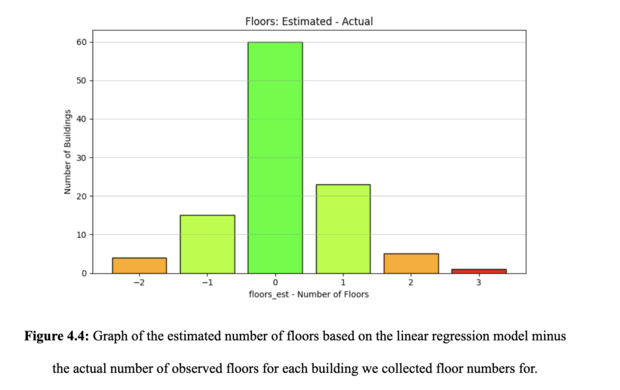

File:4.4.png| Floors: Estimated – Actual. This bar chart compares the predicted number of floors from our linear regression model to the actual observed floors. The distribution shows that the model is highly accurate: most buildings fall at 0 difference, with smaller groups at ±1 floor. Only a few buildings deviate by 2–3 floors, demonstrating that large errors are rare and limited to atypical structures.

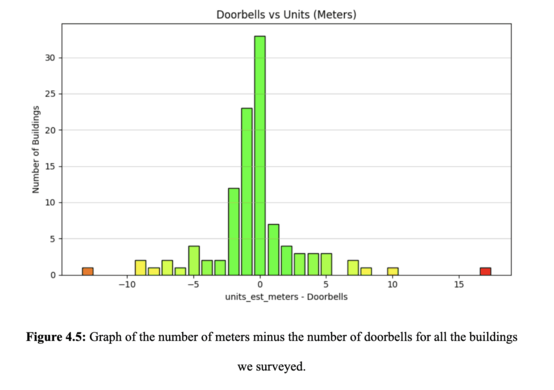

File:4.5.png| Doorbells vs. Units (Meters). This chart compares unit counts derived from water meters to those implied by doorbells. Differences cluster around 0, indicating strong agreement between the two proxies. Slight deviations (±1–5 units) appear in buildings with shared entries or multiple-unit meters, while outliers reflect unusual internal layouts. Overall, the pattern confirms the reliability of meter-based unit estimation.