Altar

For more specific information about altars in Venice, see Altars

An altar, or in Italian altari, is a tablelike construction used in the Christian church in celebrating the Eucharist. [1] Altars can range from being simple tables to intricate stone pieces with carved figures on the front and sides. These figures typically depict biblical figures or stories. The main altar of a church is a focal point of the interior, being located at the end on the nave, and the center of the transept. Larger churches may have additional smaller side altars in addition to the main altar, where masses and other religious ceremonies can be held in a more intimate setting. Altars frequently hold relics connected to saints and martyrs of the Catholic Church.

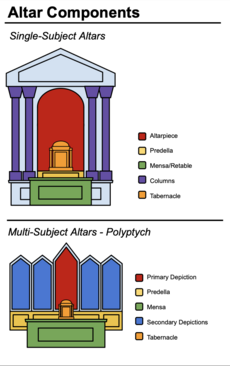

Components of an Altar

Table (Mensa)

The mensa refers to the flat piece of the altar upon which the elements used to celebrate the eucharist are placed. These are typically made of stone, but more modern mensa can also be made of wood. The front of the mensa can be decorated with carvings, mosaics, or cloth coverings.

Altarpiece (Pala d'Altare)

The altarpiece refers to the vertical portion of the altar connected to the mensa behind it and typically connected to the wall of the church. There are multiple types of altarpieces and these types are sometimes mixed. The altarpiece usually displays icons of the Catholic church or depicts a scene from biblical or religious history.

The most common kind of altarpiece is a painting (dipiti). These paintings can range from small portraits of saints to massive depictions of scenes from the life of Christ.

The less common kind of altarpiece is a polyptych, which consists of painted panels separated by folds or hinges. A polyptych consists of more than three panels, with altar pieces made of two or three panels called diptychs or triptychs respectively. These panels typically display images of saints or other religious figures. Under the polyptych, there is often a predella or platform with panels depicting the scenes from the life of a saint.

Tabernacle (Tabernacolo)

A tabernacle refers to a compartment in which the eucharist is stored. It takes the form of a metal or opauqe decorative box with an opening panel, so that the body and blood of christ can be kept without obstruction in between celebrations of mass.

The word tabernacle itself means “dwelling place.” [2]

Predella

A predella, or platform, is a panel located underneath the altarpiece which often serves many different purposes. The predella can be used functionally, as a storage container for relics, tombs, and full body displays, with inscriptions marking what the relic contains. The predella can also be used as a part of the artistic composition of the altar, displaying scenes from the Bible, or depicting miracles of the saint which the altar is dedicated to.

|

|

|

Balustrade (Balaustra)

The balustrade is a railing, typically made of stone or metal, which act as a barrier to an altar. The balustrade in front of an altar generally includes a space in the middle leaving space for a gate, through which the altar can be accessed. Certain variations of latin masses use the balustrade as a instrument of delivering the eucharist. [3]

Main Altar

In the ancient basilicas the priest faced the people as he stood at the altar. When the basilicas were adapted for Christian assemblies, slight modifications were made and the altar stood between the clergy and people. Later on the altar was placed in the apse against or at least near the wall, so that the priest when celebrating faced the east and the people were placed behind him.

Form of an Altar

There are two kinds of altars according to the present discipline of the church, the fixed and the portable. A fixed altar is one that is attached to a wall, a floor, or a column whether it be consecrated or not and in the in the liturgical sense it is a permanent structure of stone, consisting of a consecrated table and support, which must be built on a solid foundation. A portable altar is one that may be carried from one place to another and in the liturgical sense it is a consecrated altar-stone, sufficiently large to hold the Sacred Host and the greater part of the base of the chalice. It is inserted in the table of an altar which is not a consecrated fixed altar.

The component parts of a fixed altar in the liturgical sense are the table, the support and the sepulchrum. The table must be a single slab of stone firmly joined by cement to the support, so that the table and support together make one piece. Five Greek crosses are engraved on its surface, one at each of the four corners, about six inches from both edges, but directly above the support, and one in the center. [4]

Side Altars

Owning side altars was very important for many people in Venetian Society, especially patrician families, guilds, and scoule. The limited financial resources of guilds, together with the strongly devotional character of their communal life, are the reason why altar-pieces, and not other types of paintings, are what each guild acquired before trying to acquire anything else.

Guilds

The focal point of guild life was not usually the meeting-house, but the church altar, and it was here that the guilds tended to naturally concentrate their energies. Virtually all of them would by the fifteenth century have acquired patronage rights to a side altar and as well as providing funds for a priest to officiate at religious ceremonies, they also normally undertook to provide the altar with liturgical accessories and a fitting decoration. Only the very smallest and poorest of guilds could not have stretched themselves, if they wanted, to commission some sort of painted altar-piece. Whatever the size of the guild, the most pressing property was to secure rights to a church altar and a burial place for its members, and only when that had been achieved could it contemplate acquiring a meeting-house of its own. [5]

Patricians

Patrons outside the church, such as wealthy patrician families, wealthy non-patricians, or religious groups called scuole, frequently funded altars for religious and social reasons. By the early 15th century, scuole associated deeply with their respective arte, or trade guild, and became known as scuole dell’arte. While the Venetian scuole dell’arte were not as powerful or wealthy as their counterparts in other areas of Italy, the institutions offered spiritual and material support to their members. This spiritual support included special services, like memorial services for deceased members and celebrations of the feast day of their profession’s patron saint, held at their funded altar. These altars were the center point of any scuole dell’arte, and many would prioritize securing patronage rights to an altar before securing a meeting house for their group. A scuole’s altar held a very high significance within Venetian society. Records show that as much as half of a scuole’s yearly revenue could have been spent on furnishings for their altar, such as incense or candles. The other primary patrons for altars were wealthy families, which can be split into two categories: patrician families and non-noble families. For individuals and families, an altar was a way to secure prayers for their souls after their death and, in certain cases, an altar housed in a cappella, or chapel, could serve as a burial site. Non-noble families, especially those not originally from Venice, would patronize an altar as a way to show influence and assert importance within the local community and Venetian society as a whole.

Many patrons would pay to be included in the paintings of saints and biblical figures as a way to secure their legacy, as building monuments in Venice was illegal. 86 altars in Venice have been identified with credible ties to patrons.

References

- ↑ Definition of ALTAR. (n.d.). Www.merriam-Webster.com. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/altar

- ↑ https://www.catholic.com/qa/what-is-a-tabernacle

- ↑ citation needed

- ↑ Schulte, Augustin Joseph. Altar (in Liturgy). Available from http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Catholic_Encyclopedia_(1913)/Altar_Frontal.

- ↑ Humfrey, Peter, and Richard MacKenney. 1986. The Venetian Trade Guilds as Patrons of Art in the Renaissance. 128 (998):317-330.